I’ve been thinking about chimps and bananas a lot the last few weeks. Not actual chimps but metaphorical ones. With all the sport on T.V. with the commonwealth games, and having watched a couple of good BBC documentaries I have been reflecting on what seems to be a confusing dichotomy in what in sports psychology is called ‘Flow’.

Sensing ‘flow’, or ‘getting in the zone’, is what athletes strive for in terms of executing the perfect performance. According to all the definitions I have found, in a state of 'flow' everything happens easily, decisions are made almost automatically, and attention is focussed purely on the task in hand. Distractions and negative thought processes and emotions do not interfere with the event. Time is not linear but instead action and awareness are immersed in the intense present.

I would say I have experienced what I would describe as ‘flow’ a handful of times both in and out of the sports environment, but in particular I’m interested in the role emotion has to play. I can see the benefit of learning to exclude negative emotions, but I am wondering if attending to positive emotions is part of the experience, and whether becoming more aware of these positive elements can allow you to access ‘flow’ more often.

‘Flow’ or ‘zone’ experiences are difficult to achieve for many, and often require some training and practice in ‘mindfulness’, an ability to observe your own thoughts and emotions as they happen in the moment. Mindfulness is practiced to increase self-awareness.

‘Flow’ in this sense does not only belong to the sports world but is a state of being sought through meditation and spiritual practice too, as a means of de-stressing and detaching from the mind clutter of modern life, or as a path to enlightenment. In the context of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for example this awareness of thought processes and the (often negative) emotional cascade that they can trigger is the essence of the work to change a persons’ mind set. You become aware of a pattern of recurring thought and you notice the emotion that is triggered. Then, by way of training and practice, you replace that unwanted, negative thought with a counter argument, thereby sending your emotions in a more positive direction.

In many forms of therapy developing a ‘watcher’ perspective of your own thoughts and emotions is the first step. The second step is learning to intervene early enough to change unwanted patterns, emotions and behaviours.

The ‘Chimp’ comes into this realm by way of the now widely known psychiatrist Steve Peters who revolutionised the psychological approach taken by British Cyclists in the run in to the Beijing Olympics and beyond. Peters was interviewed as part of one of the BBC documentaries that inspired this post called ‘Sir Chris Hoy – How to win Gold’.

Dr. Steve Peters has created and propagated a mind management model that has successfully been applied to sport as well as other fields. In the documentary Sir Chris Hoy references the benefits he gleaned from the approach in providing the edge he needed in his final few years as a professional cyclist, and in maintaining mental focus under enormous pressure.

In cycling circles at least the basic tenets of this model have infiltrated the vocabulary, and phrases like ‘caging the chimp’ are widely understood to be references to the chimp that Peters speaks of in his model; your ‘emotional brain’ that can derail you if you don’t learn to control it (cage it).

This most basic part of the model I really like as it is something we can all easily relate to. Peters talks about the importance of self-awareness too and getting to know your chimp as a first step to keeping it in the cage. And so I have been reflecting on my own chimp who I will introduce to you here:

My chimp is motivated by play and curiosity. He wants to have a laugh and mess about and can become a bit over excitable. My chimp needs to be let out of the cage to have fun and explore fairly often, but it's important that the environment in which I let him play is a safe one so things don't get out of hand and he doesn't get hurt. Sometimes he may overstep the mark and poke a big gorilla in the ribs and then wonder why he is being chased out of the jungle when all he wanted to do was have fun and make friends. Cage my chimp too long and he will get depressed or become self-destructive. My chimp is sensitive but may seem aggressive and lash out because of the frustration of containment. He has many positive qualities associated with his personality but he can certainly derail me if I don't keep an eye on him. My chimp is a lively little fella and I am trying to find a way to manage him.

You see, the chimp part of the model is quite easy to get a handle on, but there are elements of it which for me are conflicting and frankly turn me off. I have read most of the book; 'The chimp paradox', but got lost somewhere between the 'planet of shadows' and the 'asteroid belt'. This may be my lack of persistence, or ironically my chimps' limited attention span, but there is something about the mechanisation of the human brain that Peters describes in it that leaves me flat.

Dr. Peters describes getting into the ‘zone’ as ‘getting into 'computer mode’ by becoming calm, logical and rational. He states that athletes don’t report a high emotional state during the experience but only start to feel any emotions after the event, when the realisation of what they have achieved starts to sink in. While there seems to be a lot of agreement on some of the aspects of ‘flow’, it appears that the question of whether positive emotion has a part to play during the ‘flow’ experience is up for debate.

Contrast Peters’ model with Graham Obree’s description of the flow state in conversation with Chris Hoy in the documentary:

‘I had the best computer in the world. The world’s most powerful computer…my own cerebral cortex which is tuned into every bodily function in real time. Even to this day there is no computer to compare to the human cortex…You can plug all the probes into every orifice you want and you’re not even coming close. And if you can tune into that ….from the sub-conscious to the conscious…I can feel it…I’m tuned in’.

While he too uses the computer analogy, I believe that Obree describes a very different experience. It is certainly one of heightened awareness but he also describes it as being ‘like an Albatross flying’. He seems to go into his emotions and emmerse his whole body and mind in the experience. In contrast to the more clinical ‘chimp paradox’ model Obree speaks about an elusive holistic experience where he is ‘hyper- aware’ of sensation and feedback from his body, but also is trying to find an analogy for the intangible emotions running through him which are distinctly separate from sensory information and feedback. Perhaps there is still no easily describable emotion there to speak of but there is certainly plenty of feeling.

I came away from watching that documentary wanting some sort of Q & A show where Peters and Obree go head to head to discuss and debate chimps and albatrosses from their own seemingly different viewpoints. Part of what would make that discussion fascinating for me is the fact that Dr. Peters is a psychiatrist and Graham Obree is a man who has wrestled with mental illness. And when Obree speaks about his 'flow' experience I am transfixed, but when Peters speaks of it I am left disinterested. Maybe thats' because I am naturally a more emotional than rational person. Maybe it's because my chimp is not in the cage. Maybe it's because I'm a bit mental.

I understand that the chimp model is about recognising negative or unhelpful emotions and choosing not to attend to them, but what about choosing and learning to attend to positive emotions in the flow state? What about this amazing almost spiritual connection between body and mind that Obree alludes to?

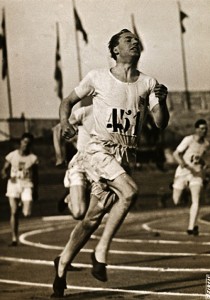

Running parallel to the Hoy Documentary on the BBC was another called ‘100 Seconds to Beat the World: The David Rudesha story’, a beautiful yet slow paced tale about the special relationship between Kenyan 800m world record holder David Rudesha and his Irish catholic coach Brother Colm. In it brother Colm refers to his religion as being central to his role as coach, such that for him, for some Godly reason he has been called to channel God through his work with young athletes.

We could of course rationalise his success with Rudisha very easily. Davids’ father was an Olympian. David and the other athletes who have passed through Brother Colms’ school have great genetics and a natural diet both in terms of food and early (often barefoot) running experience. But in this story what comes through the most is the importance of faith which seems to be a sort of irrational ‘flow’ in itself; Brother Colms faith in God and his calling, and David Rhodeshas faith in brother Colm.

I am not religious myself but I know that athletes through the ages have cited this faith running through them as a kind of transcendent experience. Most famously in the film Chariots of Fire Eric Liddel is quoted as saying: ‘I believe God made me for a purpose, but he also made me fast. And when I run I feel His pleasure’. If this isn’t a description of the positive feelings associated with ‘flow’ then I don’t know what is.

Naturally as with all the interesting subjects I doubt there is a right or wrong answer to the question 'Is there a place for any emotion in the flow experience?'

But for me I think I can draw something useful from both viewpoints as I figure out for myself how to best channel my own 'flow'. I'm certainly going to keep trying to manage my chimp, but equally I am going to keep half an eye open for an Albatross.